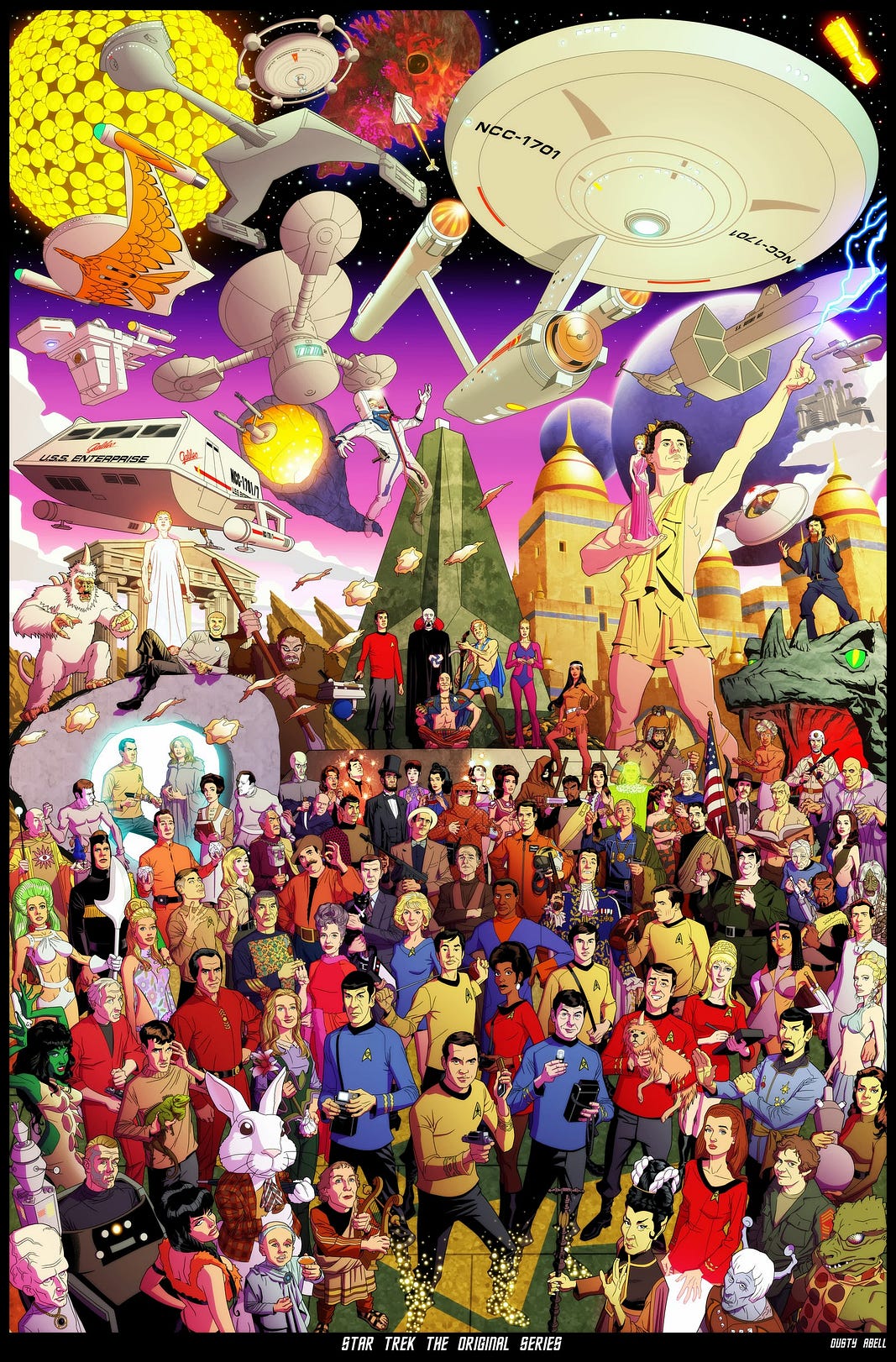

Star Trek: The Next Generation 30th Anniversary Print by Dusty Abell, Copyright © 2017, Roddenberry Entertainment Inc. Reprinted with permission. All Rights Reserved. Dusty Abell is a comic artist who has pencilled countless comic books, is an illustrator, and has been involved in the animation industry as a character designer since 2000. He has worked on productions such as Batman: Return of the Caped Crusader, Batman vs. Two-Face, Young Justice, Mike Tyson Mysteries, King of the Hill, The Official Handbook of the Invincible Universe for Robert Kirkman, the creator of The Walking Dead, and many, many others.

The first Star Trek television show, known colloquially as The Original Series, ran from 1966 to 1969. The series, produced by Paramount Television and both commissioned by and broadcast on NBC, had its moments with episodes that broke critical new ground, like the first inter-racial kisses in Season 1’s introduction to Khan Noonien-Singh, “Space Seed,” and the more frequently cited kiss between Kirk and Uhura in Season 3 episode “Plato’s Stepchildren.”

Then there were other episodes that kicked down granny’s door, broke her fine china, and peed in the foyer. Some common examples are from the third season, the premier called “Spock’s Brain,” and two weird “ensemble antagonist” episodes, a gaggle of space hippies in “The Way to Eden” described by Grace Lee Whitney (Ensign Rand) as a “clinker” and a throng of amnesiac tweens mind-controlled by a used car salesman generously blended with the ghost of a megachurch preacher in “And the Children Shall Lead”.

Series creator, Gene Roddenberry, clearly had luck on his side. NBC paid to have a pilot made and didn’t like it, but made the unusual decision to commission a second, which would become the Star Trek we know today. That luck, and an “organic” fan write-in campaign, would get them through a cancellation threat in the middle of the second season, but a second “organic” campaign would fail, and Star Trek was cancelled during the third season.

Star Trek however would go on to become quite popular in syndication, something I can directly attest to as I was a young lad in the 70’s. The intense popularity would prompt Roddenberry to team up with Filmation to create an animated series that ran on Saturday morning for twenty-two episodes over two seasons in 1973 and 1974. Later, the animated series that was broadcast also as Star Trek would become known as Star Trek: The Animated Series, and would represent the unofficial fourth and fifth seasons of The Original Series, at least according to the most devoted Trekkers/Trekkies.

It wouldn't be until 1979 that The Motion Picture would propel Star Trek from the syndication juggernaut it had become into an honest-to-goodness, multi-format franchise.

Let’s slow our roll a bit, my peeps. If I were to detail the development and production of ST:TOS, this article would take you a few hours to read. Instead, I’ve outlined a rough sketch of events sufficient for you to have context. If you’d like to know more about the history of Star Trek, check out the Wikipedia pages where there is an embarrassment of content, including entire pages for each episode of every series. At the very least, peruse the pages for The Original Series and The Animated Series, as those tales are fascinating. -Ed.

Star Trek is an American science fiction media franchise created by Gene Roddenberry, which began with the eponymous…en.wikipedia.org

The adventure begins… again

Star Trek: The Motion Picture managed mixed reactions from fans and critics alike, often noting that it lacked in traditional action set pieces and contained far too many special effects shots, a concept that seems alien in 2022. It turns out that the film was based on an episode of a cancelled Star Trek: Phase II series expanded into a feature film, which might explain why there are many long, experiential sequences that pad the run-time. It’s difficult to get two hours of story out of a teleplay meant to fit into a one-hour time slot. Despite this, fan interest was quite strong. The film made enough at the box office to warrant a sequel, and that turned out to be just what the struggling franchise needed. What came next would become one of the most beloved films of all time, Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan.

That simple twist of fate which brought together the right people at the right time to create something that astonished and delighted fans of the original series would form the new foundation of an epic theatrical run and almost enough energy to spin Star Trek into four new TV series. Each series would be less popular than the last with TNG and DS9 battling for most beloved, but only TNG’s crew shifted to cinematic releases, bowing with 1994’s Star Trek: Generations.

NOTE: We Trek fans love our acronyms. For the remainder of this article I will be referring to each series by its acronym. The general rule of thumb, if you’d not noticed yet, is ST for Star Trek followed by a colon, then an acronym from the series title, like so: Star Trek: The Next Generation (ST:TNG), Star Trek: Deep Space 9 (ST:DS9), Star Trek: Voyager (ST:VOY), and Star Trek: Enterprise, which didn’t get a catchy acronym that would stick. As such, the original series would be TOS or ST:TOS and the animated one, TAS or ST:TAS. In context, you drop the ST: to leave the remaining unique identifier. -Ed.

Paramount weren’t just twiddling their thumbs following the end of TAS, as they would release four theatrical films over the next seven years, 1979’s Star Trek: The Movie, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan in 1982, Star Trek III: The Search for Spock in 1984, and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home in 1986. The first four films primarily focused on the TOS cast, but also started roughly sketching out the Trek universe, establishing many of the rules, the foundations of the United Federation of Planets, and relationships between the races, both complementary and contentious. You know, world building.

Energized by the popularity of ST:TOS in syndication and the first four feature films, Wrath of Khan and Voyage Home proving to be box-office blockbusters, Paramount began to develop a new television series that would become Star Trek: The Next Generation. Unhappy with the offers from ABC, CBS, and NBC and passing on an anemic offer from the newly minted FOX network, Paramount instead opted to retain full control, offering Star Trek: The Next Generation to independent stations under a barter syndication contract known as First-Run Syndication.

An explanation of Barter Syndication excerpted from the TNG Wikipedia entry: The stations sold five minutes of commercial time to local advertisers and Paramount sold the remaining seven minutes to national advertisers. Stations had to commit to purchasing reruns in the future, and only those that aired the new show could purchase the popular reruns of the Original Series.

For the new show, the TNG production team developed a more refined version of the episodic format established by TOS, where episodes would show a crew working together to solve problems through the lens of current events and cultural sentiment of the time, many of the themes being universally familiar. Far more than a mere monster-of-the-week format, Roddenberry wanted to create a universe where interpersonal conflict was a thing of the past, establishing in the production bible that crew mates weren’t guided by greed, lust, or power, opting instead for a more congenial fellowship.

The first season didn’t go well. Many of the writers from TOS were producing scripts that didn’t fit into Gene’s ideals and, as a result, Roddenberry reportedly “rewrote” the first fifteen episodes of the first season so they would adhere to his rules. Critics were unimpressed. DVD Journal’s Mark Bourne said at the time, “A typical episode relied on trite plot points, clumsy allegories, dry and stilted dialogue, or characterization that was taking too long to feel relaxed and natural." Patrick Stewart’s acting was applauded, however, and a number of key serial story arcs would be introduced, as well as some of the series’ most iconic recurring characters such as the god-like Q and Data’s evil twin brother, Lore.

“A typical episode relied on trite plot points, clumsy allegories, dry and stilted dialogue, or characterization that was taking too long to feel relaxed and natural.”

Following a debut season that would have seen a lesser property cancelled, TNG would go on to become one of the most influential television shows of all time and establish the tone and values for the next two decades of Trek.

From 1987’s launch of TNG until the premature cancellation of Enterprise in 2005 Star Trek was kind of a big deal. Some Trek luminaries regularly graced the pages of gossip rags, People, TV Guide, and other media outlets of the time, filled with glitzy paparazzi photos and talk about coming episodes. TNG had transitioned to feature films rather seamlessly with First Contact being the block buster it was and the hype around the new Trek for a new millennium.

2002’s Star Trek: Nemesis, the fourth film in the TNG run, didn’t do well, however, and the franchise would go mostly dormant for another seven years before J.J. Abrams 2009 Star Trek introduced a new take on the characters from TOS. Not only did “JJ” (I’m not typing those periods every time, people) bring a whole new style and tone to the franchise, but would create a new alternate future-history with the so-called Kelvin Timeline.

This radical departure from established canon had two significant effects. One, clearly unhappy with the retro-future chic of i, JJ dragged NCC-1701 “Enterprise” far, far, FAR into the future, one of the principle hallmarks of the reboot. This also had an unintended effect. When Paramount was seeking to reinvigorate the Trek TV franchise for their new streaming platform in partnership with CBS (now Paramount+) they leaned into the esthetic that JJ brought with the films, kickstarting the multi-season debacle that is Discovery, but I’ll get to that soon enough. Two, it kicked the original canon to the curb in favor of a more bombastic, action-oriented approach helmed by a collection of actors portraying, albeit excellently, caricatures of the beloved characters they were reprising, while lacking much of the nuance and “humanity” that Kirk, Spock, Bones, Scotty, Uhura et al. brought to the table through all of the films.

JJ’s 2009 Star Trek would use the Trek wireframe, but fill it with action set pieces and coded witty banter designed to stereotype the characters to whom they were supposedly paying homage. American audiences ate it up like so much candy and, as it is in today’s Hollywood, two more films were made, neither of which were very good. Certainly gorgeous and packed to the gills with action set pieces, but still lacking any of the true soul of Star Trek.

So, what IS Star Trek?

Well, one thing Trek is not is any one thing. I’m not great with philosophy. To make this easier on me, watch this fantastic video from Wisecrack, a YouTube channel that discusses all manner of things through the lens of philosophy.

The one thing that Jared (you should watch the video, seriously) glossed over was the fact that no one ideology rules anything. Even if the Borg were to exist, they would not be able to create an entirely homogeneous universe from end to end. In canon, the “Q” would likely stop them, as we “lower” beings, at the very least, provide the Q some modicum of entertainment, while recognizing that change in inevitable.

Take the Borg Queen as an example. She is, in a very real sense, a singular force who has her own wishes and desires and she obsesses over them to the point of her own destruction, as we see in Star Trek: First Contact. She presented as an avatar of absolute dictators like North Korea’s Kim Jung Un, an individual who, through a force and terror structure handed down to him by his progenitors, decides the fate of every single soul living within the borders of “his” country.

And yet, if this was the root of what makes Star Trek, then the Borg would be the only antagonist to face the Enterprise crew, backed by the ideals of The Federation of Planets and its all-encompassing Prime Directive. No, Star Trek is so, so much more, as through 700+ episodes of TV and a bevy of feature-length films (minus JJ’s works) we see depictions of just about every ideological stance humans have invented as seen through it’s own lens; humanism.

Trek, then, imagines an egalitarian future that is not free of crime and sorrow and violence, but one that responds to those things with restraint and understanding and, as necessary, force. Does Star Trek represent a true utopia? Of course not. As with the Borg, it’s simply not possible. Living beings, regardless of how well we might be able to work together, will always have differences, and from that will spring all manner of conflict, and we all know what happens when there’s conflict. Unresolved conflict eventually leads to violence. Always…

But there’s more…

Trek isn’t just a platform for developing thesis around philosophy. There are more esoteric aspects of the functional aspects of how Pre-Abrams Trek was produced. The easiest way to illustrate that is with a bullet list:

- Tolerance — the bridge crew in TOS included a Russian… DURING THE COLD WAR. The aforementioned black+white kiss happened on TOS. In all things, the crews of Trek are tolerant until someone’s rights are being abused, at which point they tend to break the rules to make it as right as possible.

- Empathy — the protagonists of Trek feel bad for others who are being hurt, but retain their human flaws. TOS Kirk wished for the death of the Klingon race after one Klingon killed his son, but he would later fight tooth and nail to save them. When one of the crew is taken over by a malevolent force, something that happens frequently, they don’t judge the individual for something they could not control. When they get a distress call, they rush to help. Caring for others comes first.

- Logic — paramount to Vulcan culture is the suppression of their decidedly hyper violent emotional aspects to lean into logic, as cold and impersonal as it is. And yet, that doesn’t override the egalitarian humanism. It complements it. Kirk, Picard, Sisko, Janeway, and Archer had foils in the form of their bridge crews, each of which challenged their initial impulses with alternative views of the same events occurring in each episode. These captains would then distill their collective brain power into a string of decisions that would result in a desired outcome, typically one that would save or, at the very least, improve the lives of the people determined to be in need.

- Technological Egalitarianism — not necessarily ideological in nature, the technology and science presented throughout the Trek universe, up until JJ Abrams took the helm, was an operational expression of critical thinking. Within the rules of Trek, the crews would work together to figure out a problem, determine the best course of action to correct it, and implement a plan to achieve the desired goal. This would often require the use or manipulation of some technological aspect of the Trek universe, and Trek production teams would use real scientists to paint at least a somewhat accurate scientific solution based on as much reality as possible. There were, in almost no uncertain terms, any “magical” solutions that just worked without making some kind of sense. Some episodes slipped. Nobody’s perfect.

- Individualism, not Socialism — Contrary to popular belief, a Trek future is not one of Socialism but of empowered, cooperative individuals enabled by an egalitarian collective understanding. This can be illustrated by the simple fact that, when faced with a crisis, Trek Captains break the rules to do the right thing and, while they pay the consequences, they are never diminished as an individual. We see this most consistently in Star Trek: Voyager where Captain Janeway no longer has a direct connection to The Federation. And yet, despite the vast gulf of space between Voyager and Earth, the crew struggles to maintain the values of the Prime Directive.* This shows the audience that individuals, not socialist constructs, are the ultimate arbiters of applications of their own power. There are rules, but smart people know that there can’t be enough rules to satisfy all issues, so some of them must be bent on occasion.

* Thanks for the inspiration, CameronHarwick.com

In a impossible nutshell, Trek is… complicated, and it’s fiction that merely illustrates an imagined future where equality is paramount, life is sacrosanct, power is moderated, self is recognized, and about a billion other truisms. And yet, one ideal rises above all others; humanism. I must call it humanism because I don’t know a word that describes the same thing as applied to multiple sentient alien species. Star Trek, as a whole, does its damnedest to make everyone matter.

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Reboot…

A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum is a musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and book by Burt…en.wikipedia.org

Much like the farcical Broadway show with a very similar name from 1962, JJ’s Star Trek is itself a farcical take on the original canon, starting with TOS and ending with Enterprise. “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum” was inspired by ancient Roman farces and heavily flavored with vaudevillian antics.

While the musical does lean into social commentary and satire, JJ’s intended his Trek to be a reintroduction of the Trek Universe to newcomers, according to Abrams himself. A read through the Wikipedia entry for the 2009 film titled simply Star Trek is telling. The “Production” section is littered with casual Hollywood justifications for all of the changes made, and how JJ’s team just knew it would work to make the characters relatable and the story exciting.

Never mind that these characters, established over fifty-plus years of material, had already been established, deeply relatable, and I’ll be damned if Trek wasn’t already exciting.

Star Trek is a 2009 American science fiction action film directed by J. J. Abrams and written by Roberto Orci and Alex…en.wikipedia.org

So, canon be damned, JJ and Co. decided to effectively toss everything nuanced and substitute common, work-a-day Hollywood tropes.

I think it’s the dismissive insult of flippantly casting aside decades of work by hundreds of cast and crew to maintain canon spanning fifteen productions that bothers me the most. The universe of Star Trek is as rich, deep, and diverse as Tolkien’s Silmarillion, from which can spring an endless array of possible stories that would have thrilled and engaged moviegoers, but instead we were served an admittedly gorgeous extended episode of Miami Vice in Space packed stem to stern with eye-straining lens flares accompanying Michael Bay-inspired action set pieces. If, however, you watch it like watching a Star Wars movie, ironically or tragically the preferred franchise of JJ Abrams, it is a fun film.

The fun would end with Star Trek Into Darkness, though, as it would tackle rebooting the much beloved and revered character arc of one Khan Noonien Singh, utterly annihilating it in the process. Khan, now a white dude in the form of the otherwise brilliant Benedict Cumberbatch, is overwhelmingly unrecognizable, even when we learn his character’s true name and purpose. Nothing about Into Darkness resonates in any way, shape, or form with Star Trek: Wrath of Khan aside from the exceedingly clumsy tropes that were yanked from the original source material and turned into a “twist” at the end that again insults any and all fans with even passing knowledge of the landmark Trek film.

Star Trek Beyond, directed this time by serial Fast & Furious helmer Justin Lin, is on an entirely different level of tangent as it features one of the largest structures ever built by the Federation, Starbase Yorktown, an impossibly huge, transparent behemoth that was clearly [pun alert] unrealistic in light of the fact that this is supposed to have been constructed during James T. Kirk’s early years in the captain’s chair and therefore, prior to events in The Original Series.

And if all this wasn’t enough, the mood around Trek was already darkened by the passing of screen legend Leonard Nimoy (TOS Spock) and that actor Anton Yelchin (who played a delightful Pavel Chekov) had been killed in a tragic vehicle accident a month before the film’s release.

Despite positive critical and audience reviews, however, Beyond effectively bombed at the US box-office as it couldn’t hold up to pressure from Jason Bourne and Suicide Squad. It’s also quite likely that the decline in ticket sales was due to the existing fan base starting to have an increasingly bad taste in their mouths from the effects of JJ’s radical changes to canon. That sour taste would be the unwanted gift that just kept on giving as, a few years later, CBS and Paramount would start to spin up new streaming properties, starting with Discovery which would be the keystone to their line-up on the then shiny new CBS All Access, now re-branded as Paramount+.

J.J.’s Series of Unfortunate Events

Mirroring the excessively disastrous manner in which the blockbusting success of Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight film trilogy would inform Warner’s DCEU with overly dark and brooding tones that weren’t appropriate for the IPs they were applied to, JJ’s Trek films and Kelvin timeline would inject a cancer throughout Paramount’s Trek productions, namely Discovery. Read this excerpt from the Wikipedia entry for the series:

The series begins around ten years before the events of Star Trek: The Original Series, when Commander Michael Burnham’s recklessness starts a war between the United Federation of Planets and the Klingon Empire. She is court-martialed, demoted, and reassigned to the USS Discovery, which has a unique means of propulsion called the “Spore Drive”. After an adventure in the Mirror Universe, Discovery helps end the Klingon war. In the second season they investigate seven mysterious signals and a strange figure known as the “Red Angel”, and fight off a rogue artificial intelligence. This conflict ends with the Discovery traveling to the 32nd century, more than 900 years into their future.

The USS Discovery finds the Federation fragmented in the future, and investigates the cause of a cataclysmic event known as the “Burn” in the third season. Burnham is promoted to captain of Discovery at the end of the season, and in the fourth season the crew helps rebuild the Federation while facing a space anomaly that causes destruction across the galaxy.

As a life-long Trekkie, this reads like the fever dream of a nine year-old who watched a few episodes of TOS for the first time while playing with crayons while binging on Mountain Dew and Ho Ho’s. The thing that frustrates me the most however is the “Spore Drive”, a magical solution which, like the improbability-powered Heart of Gold from Douglas Adams’ satirical and hilarious Hitchhiker’s Guide to The Galaxy books, allows the titular Discovery to instantly jump anywhere, just with more accuracy and fewer fantastical, physics-defying side effects (like turning into couches or being made of yarn until improbability normalizes.) And how, in a time occurring before the events of TOS, do they manage this? Why, with magical, space-breathing giant tardigrades, of course.

I’m not kidding.

Yes, JJ. Magical space yeti bears. Seems legit.

In short, JJ’s ridiculously callous abandonment of the core values and world building established over 50 years of Star Trek canon on television, the big screen, books, comics, and video games transmogrified the franchise into a caricature of itself. Paramount clearly felt that the popularity of 2009’s Star Trek film meant that’s what people wanted to see for Trek’s future.

I honestly don’t want to talk about Picard, as much as it pains me to say so. It’s just an expensive disaster of a show that learned everything from JJ and finally had to end with a 3rd season that both delighted and horrified long-time fans. The following article gives you a good rundown of the issues.

So, what now?

The original title to this article was going to end with “…and how to fix it.” It seems, however, that I don’t need to offer any suggestions. Paramount seems to have gotten the message.

Star Trek: Lower Decks would kick off things in a very unexpected way in August of 2020, just as the Pandemic was kicking into first gear. As you can likely see, it’s animated, but it’s not for kids. It’s what is currently termed Adult Animation, as in Family Guy, Rick & Morty, and BoJack Horseman, to name a few, and yet it hews to canon and convention, if unconventionally. It’s well worth a watch.

If that wasn’t weird enough, October 2021 would see the premier of Star Trek: Prodigy, this time for a younger audience and getting Kate Mulgrew to voice Captain Kathryn Janeway, the character she played for seven seasons of VOY. It is a surprisingly well written premise that explores their part of the universe following the same rules as a regular Trek series from a very unique perspective. It’s wonderfully fulfilling for humans of any age.

Then, in a turn wholly unexpected, there came Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, which has brought an all new take to TOS and TNG style story telling with their heads firmly in canon. In all honesty, I expected to be treated to something akin to Discovery for SNW, but my wife and I were shocked, I tell you. From the first moment, the series has honored almost everything I ever wanted in a new Trek series since Enterprise, all while delivering a fresh, new spin on the episodic formula.

And all without falling too far into the traps of JJ’s Kelvin-verse. Sure, the sets are phenomenal and appear far more advanced than TOS, but they’ve dialed out the magical clap-trap and the eye-searing lens flares to powerful and enjoyable effect.

I won’t spoil any more. Just watch it.

The obligatory summary

There’s really not a lot to say, but thanks to all of the people working on the productions of Lower Decks, Prodigy, and SNW. Your love of the Trek Universe honors the fans who have come to love Star Trek over the past half Century.

Additionally, I believe it’s important to deconstruct the things that break so we can understand why they break, or in this case, were broken.

That pretty much sums it up. Hope you enjoyed reading :)

---